Born in 1963 in Griffithstown, UK, he lives and works between Bolchlan and London, UK.

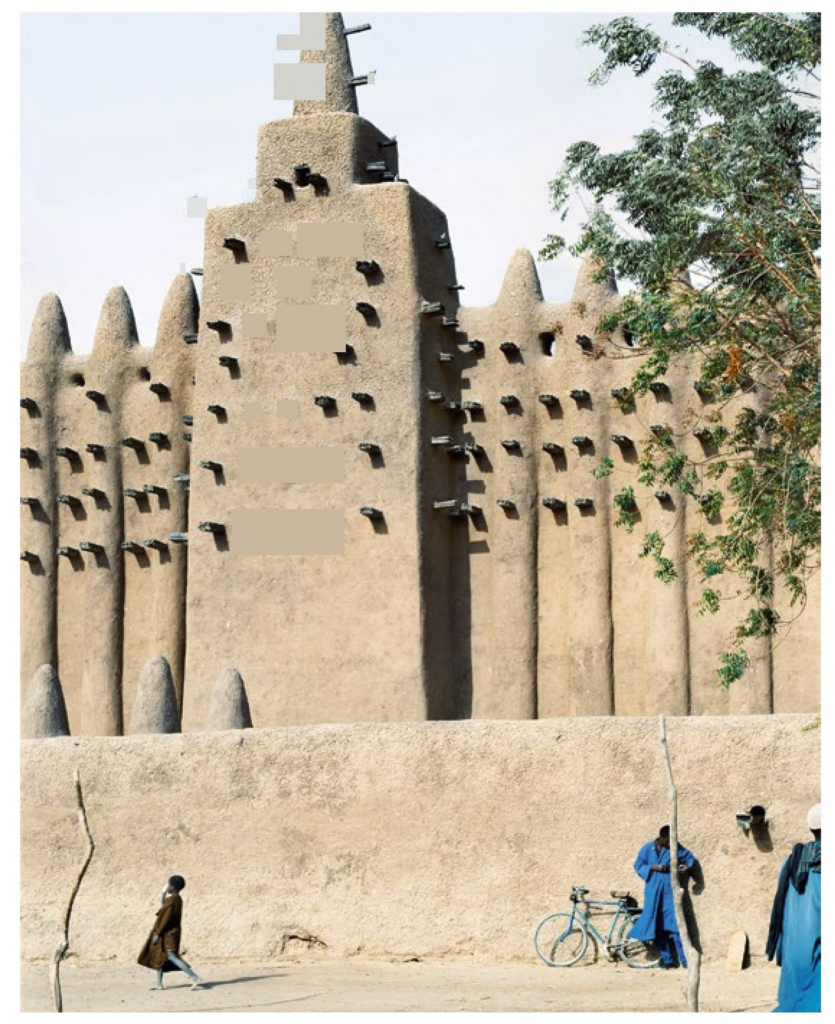

Butabu

1999-2000

Trained as a historian at University College London, James Morris originally considered becoming a documentary filmmaker. Through film he discovered his affinity for the more unencumbered process of photography as well as the control and aesthetic offered by the still image. His photographic work is rooted in a fundamental interest in architecture and built environments, which has taken him to the Middle East and Africa, including the Sahel region. Many of his projects are pursued over an extended period, during which he explores the layers of history evident in a landscape, whether that of Egypt, Mali, London, or Morris’s native Wales.

The photo series Butabu (1999–2000) stems from the photographer’s travels through multiple countries in West Africa in the years 1999 and 2000, including Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Togo, Benin, Ghana, and Burkina Faso. Morris explored far-flung villages and towns with the help of a local guide. His photographs show the richness of forms and textures in vernacular mud-brick architecture, and its range of applications: from a domestic space to a traditional ruler’s audience rooms and the minarets of mosques. The title Butabu stems from a word in the language of the Batammaliba of Togo and Benin for wetting the earth before building. Made of dried mud, these structures require consistent maintenance, and the wooden beams seen protruding from the façades of some buildings are not only decorative but serve as scaffolding to facilitate upkeep and repair.

The wealth of this architectural tradition dates back at least to the period when trading caravans crossed important political and cultural centers of the Sahel, connecting it with the Islamic world further east, and before these routes were eclipsed by the Portuguese ports established along the western African coast in the fifteenth century. Historically the builders of this architecture were neither anonymous, nor were its influences utterly Indigenous. Guild-like castes of famed master builders still pass knowledge down across generations, and Islamic, Berber, and, later, French colonial impetuses can be traced throughout the region. Today the biggest threat to these magnificent buildings is modernization and the use of industrial building materials. Simultaneously many contemporary African architects continue to be inspired by the striking and expressive aesthetic of this architectural heritage.