He was born in 1935 in Karachi, Pakistan, and lives and works in the British capital, London

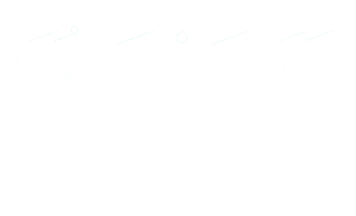

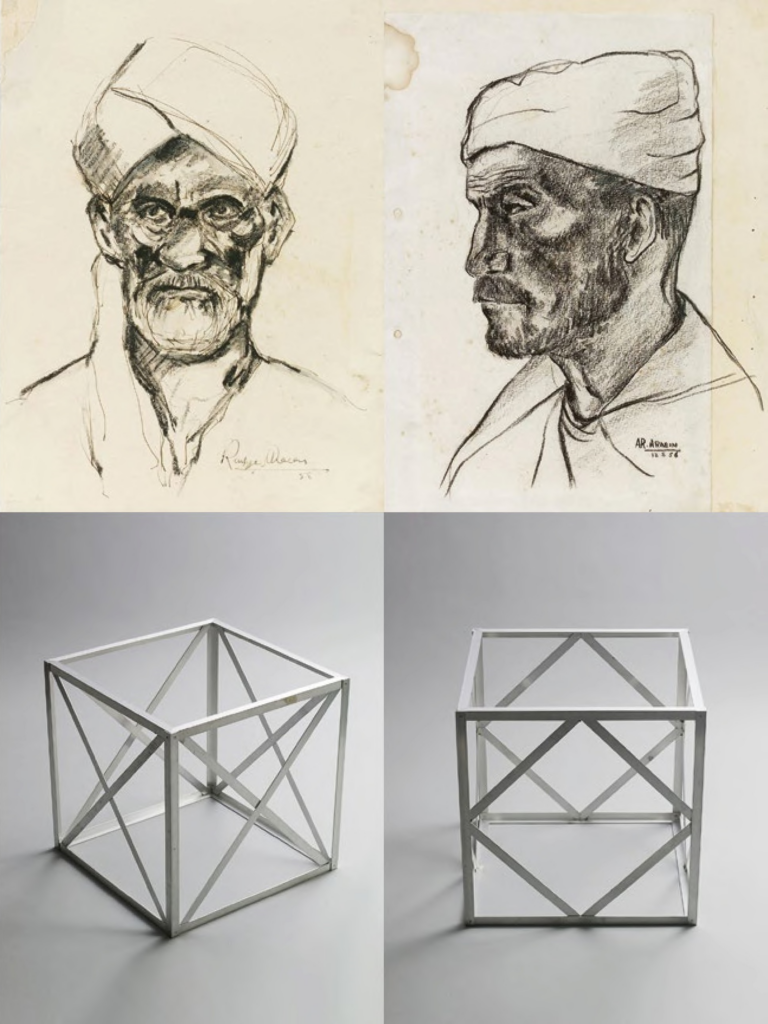

People of Karachi 1955-58, The One that Could not Float Away 1970, Cube as a Sculpture 1966/2020

Based in London since 1964, Rasheed Araeen is a pivotal figure in postcolonial art and art history. Araeen initially trained and worked as a civil engineer, and he incorporated materials and methods used in this context into his early art practice. In parallel to his art, which ranges from Minimalist and geometric sculptures, reliefs, and paintings to participatory installations and performances, Araeen has countered the Eurocentrism of mainstream art institutions and histories through criticism, publishing, and curating exhibitions. He is most widely recognized for founding (and editing) the influential journal Third Text in 1987 and for organizing the groundbreaking 1989 exhibition The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Postwar Britain at the Hayward Gallery in London, which showcased the unacknowledged contributions of immigrant artists to postwar British art.

Among Araeen’s earliest extant works, People of Karachi (1955–58) comprises thirty portraits he made during informal drawing and painting sessions in Karachi. Despite their realist style and subject matter, they demonstrate his early interest in line as the basis of form, as later reflected in the Minimalist sculptures he made following his arrival in London. His earliest such works, which he dubbed “Structures,” consisted of simple geometric compositions made of steel I-beams, painted blue or red. Araeen’s Cube as Sculpture (1966/2020) consists of twelve identical, skeletal, and white aluminum cubes arranged in a neat three-by-four grid. Araeen’s signature addition of diagonal struts to each of the cube’s faces, possibly inspired by the complex geometries found in traditional Islamic art and architecture, introduced a dynamic rhythm into the otherwise static cubic form. These early works form an important and long overlooked contribution to the history of modern sculpture.

By the end of the 1960s, Araeen had begun experimenting with geometric forms as prompts for participation and collective action. Chakras (1969–70) involved throwing fluorescent red wooden discs into a water- way close to his studio in St. Katherine Docks, London. It was the first of a series of related works: ephemeral and sometimes participatory actions that he documented in photographs such as The One That Could Not Float Away (1970), in which the disc’s simple geometry served as a foil for the unpredictability of the environment. This growing openness to contingency and context fed into the more politically charged and confrontational artworks and performances of the decades that followed.