SAMMY BALOJI

Born 1978 in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, lives and works in Lubumbashi and Brussels, Belgium

Aequare: the Future that Never Was

2023

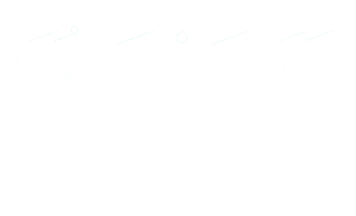

Sammy Baloji is a photographer and filmmaker who documents the long shadow of extractive colonialism. The Democratic Republic of the Congo officially gained its independence from Belgium in 1960, but in many ways the linked exploitation of its people and the environment never ended. Through diptychs, collage, and other juxtaposition techniques, he highlights how the brutalities of direct rule morphed seamlessly into economic imperialism. These effects are particularly felt in the mineral-rich mining stronghold of Katanga, Baloji’s native region, whose cultural, industrial, and architectural inheritance is at the heart of his practice. In 2008, he co-founded the Lubumbashi Biennale.

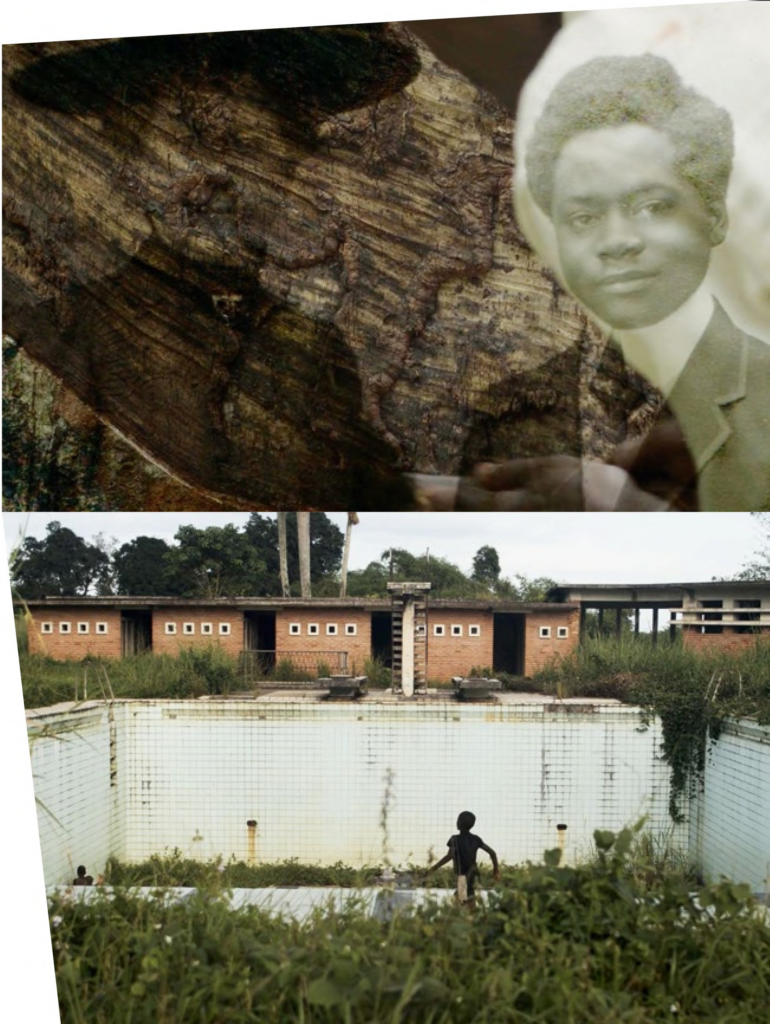

Blending Belgian newsreels from the 1940s and 1950s with present-day footage, Baloji’s video Aequare: the Future that Never Was (2023) depicts an agricultural research center in colonial and post-colonial times and makes clear just how much has remained the same over the decades. The National Institute for Agronomic Study of the Belgian Congo was established in 1933 to leverage scientific research in modernizing Indigenous agrarian practices. The colonizers wanted to make Congolese land, already showing signs of soil depletion from overcultivation, even more productive, profitable. They wanted, as a voice-over near the end of the film suggests, to tame and civilize the land, along with its people—and simultaneously frame this as a humanitarian service.

Since then, the center has been nationalized and changed its name, but land, like people, bears witness to the ravages of empire. The European scientists and their families are gone; now local children play in the same pools, presently empty and overgrown, while laboratories sit unused. The evidence of decline is everywhere: vehicles and once meticulously maintained archives are rusty and musty—one can smell the dust through the screen—but every new frame feels like a perfect match cut, so strong is the sense of continuity. Despite the colonizers’ best attempts to clear the rainforest for cash crops, it has grown back. All the life that remained out of frame in the propaganda reels is now in view, from teeming insects to river fish and local residents. Everything remains calm and lush and beautiful.